Hello, Frisco!

Ragtime Songs

Performed by Miss Ann Gibson with

Frederick Hodges, piano

Notes on the Songs by Frederick Hodges

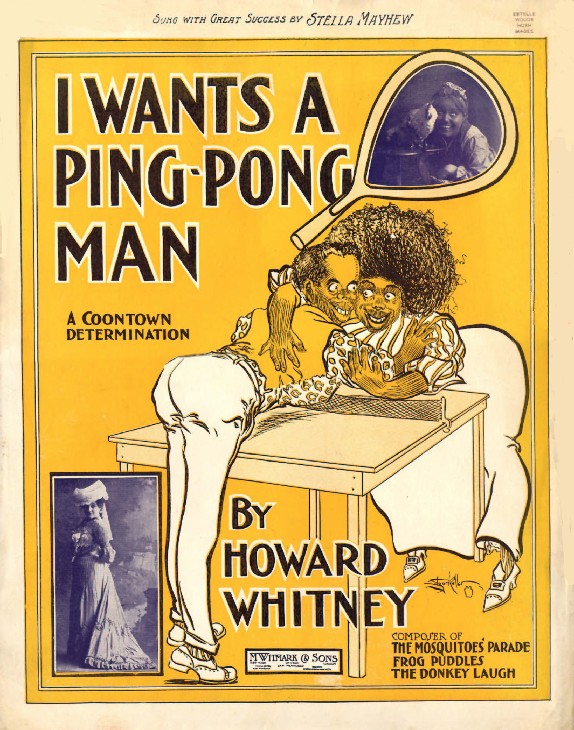

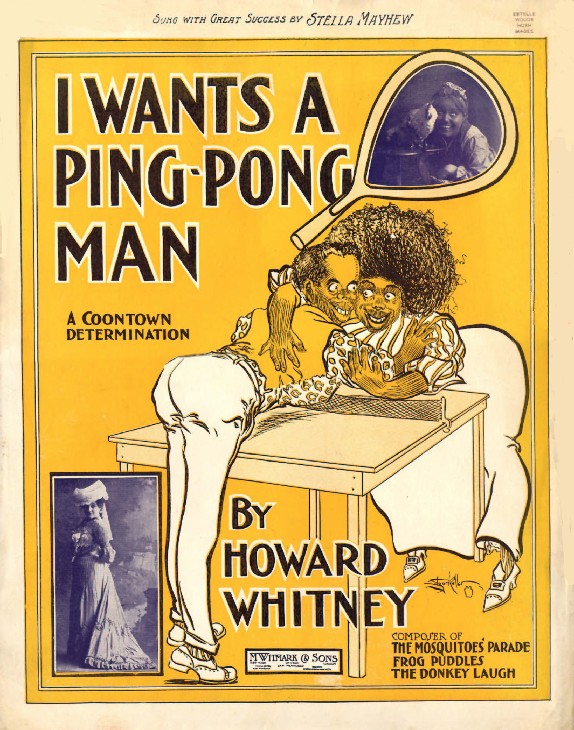

“I Wants A Ping Pong Man” Lyrics

and Music by Howard Whitney

Copyright 1903 by M. Witmark

& Sons.

The world of coon songs is largely

misunderstood today, but it bears noting that many of the best coon songs

were written by Blacks for Black performers to sing in Black Vaudeville

houses. Great Black composers such as Paul Laurence Dunbar, James Reese

Europe, Rosamond Johnson, Will Marion Cook, and Ernest Hogan, to name but

a few, wrote coon songs. Scott Joplin himself penned coon songs, including

the original song version of “The Ragtime Dance.” Still, many of the infamous

and thunderous condemnations of ragtime as corrupt and immoral were really

condemnations of the salty lyrics found in coon songs. “I Wants A Ping

Pong Man” is among the mildest and most entertaining of coon songs, bristling

with topical humor and genuine ragtime rhythms. It celebrates the growing

popularity of ping pong, or table tennis. The game has its origins in England

as an after-dinner amusement for upper-class Victorians in the 1880s. Mimicking

the game of tennis in an indoor environment, everyday objects were originally

enlisted to act as the equipment. It was not until the early 1900s that

manufacturers standardized the ball and paddle and made them commercially

available. The game was relatively new to the United States in 1904, but

Whitney enjoyed spoofing it in his song by pretending that it had reached

the Black communities and was now used as a measure of a man’s fitness

as a suitor. Howard Whitney was a composer of little piano pieces and also

contributed songs to a couple of Broadway musicals in 1904, The Royal Chef

at the Lyric Theatre in New York and also to the flop Flo-Flo, starring

Stella Mayhew.

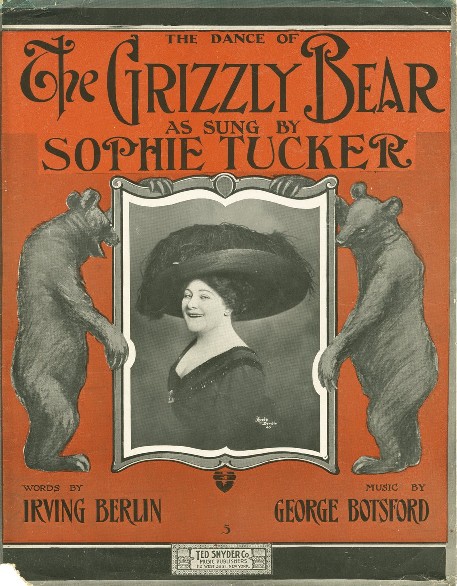

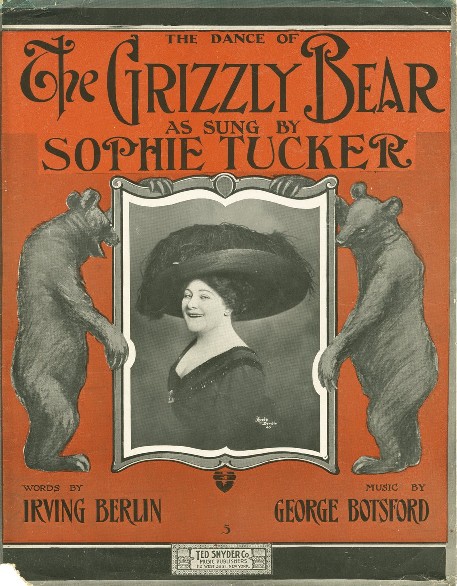

“The Dance Of The Grizzly Bear”

Lyrics by Irving Berlin and Music by George Botsford

Copyright 1910 by Ted Snyder

Co.

“The Dance Of The Grizzly Bear” started

its life as “The Grizzly Bear Rag” piano solo by noted ragtime composer

George Botsford, who was also a staff pianist at the publishing house of

Ted Snyder Company. Its immediate popularity prompted publisher Ted Snyder

to capitalize on the success of the piano rag by having his staff lyricist

Irving Berlin write words for it. While the piano rag was merely an instrumental

without any descriptive intent, Berlin’s coon song lyrics logically describe

the Grizzly Bear as one of the many animal dances that was sweeping the

nation at this time. The grizzly bear dance appears to have originated

in San Francisco, along with the Bunny Hug. In essence, it consisted of

imitations of the movements of a dancing bear. In the Ziegfeld Follies

of 1911, Fanny Brice danced the grizzly bear in a special production number

titled “The Barbary Coast.” The grizzly bear dance was frowned upon at

society dances due to its unsophisticated gestures and low associations.

On July 22, 1913, a dance card from the Exposition Park Dancing Pavilion

in Conneaut Lake, Pennsylvania warned patrons that the “Bear Dance” and

Turkey Trot would not be tolerated.

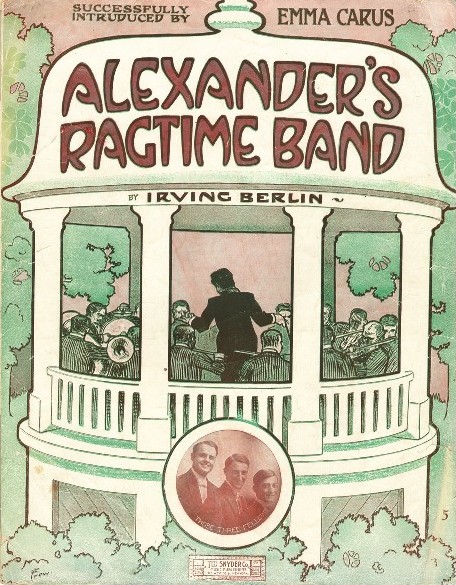

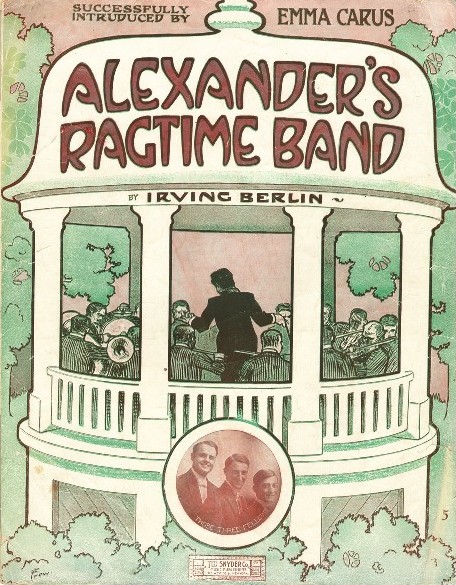

“Alexander’s Ragtime Band” Lyrics

and Music by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1911 by Ted Snyder

Co. Inc.

“Alexander’s Ragtime Band” was the

first big hit for Irving Berlin (1888-1989), earning him the title “The

Ragtime King.” The song became a national craze when the great Emma Carus

performed it in Chicago. The song then spread across the country and sold

over a million copies in just a matter of months. As wonderful as the song

is, there is considerable controversy about its origins. Scott Joplin was

convinced that Berlin stole the melody line of the verse from “A Real Slow

Drag,” a song from his opera Tremonisha, which he showed to Berlin at the

Crown-Seminary-Snyder offices, where Berlin was working in 1911. Berlin

kept the manuscript for quite a while before returning it to Joplin, declining

the opportunity to publish the opera. Joplin was shocked a few months later

when “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” came out, crying “That’s my tune!” Berlin,

of course, denied any wrongdoing. Joplin was then forced to make slight

revisions to “A Real Slow Drag” in order to avoid being charged with plagiarism

in turn. These revisions notwithstanding, the similarities between the

two songs remain striking. Whatever its origins, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”

is terrific. Its enduring popularity was demonstrated in 1938 when Twentieth

Century-Fox produced a hit musical film of the same name, starring Alice

Faye and Tyrone Power. The film spun an elaborate and highly entertaining

fiction about the origin of the song. Much like MGM’s Easter Parade of

1948 and Twentieth Century Fox’s There’s No Business Like Show Business

(1954), Alexander’s Ragtime Band was largely a vehicle for Irving Berlin

to license his early catalogue of songs — at tremendous cost — to Hollywood.

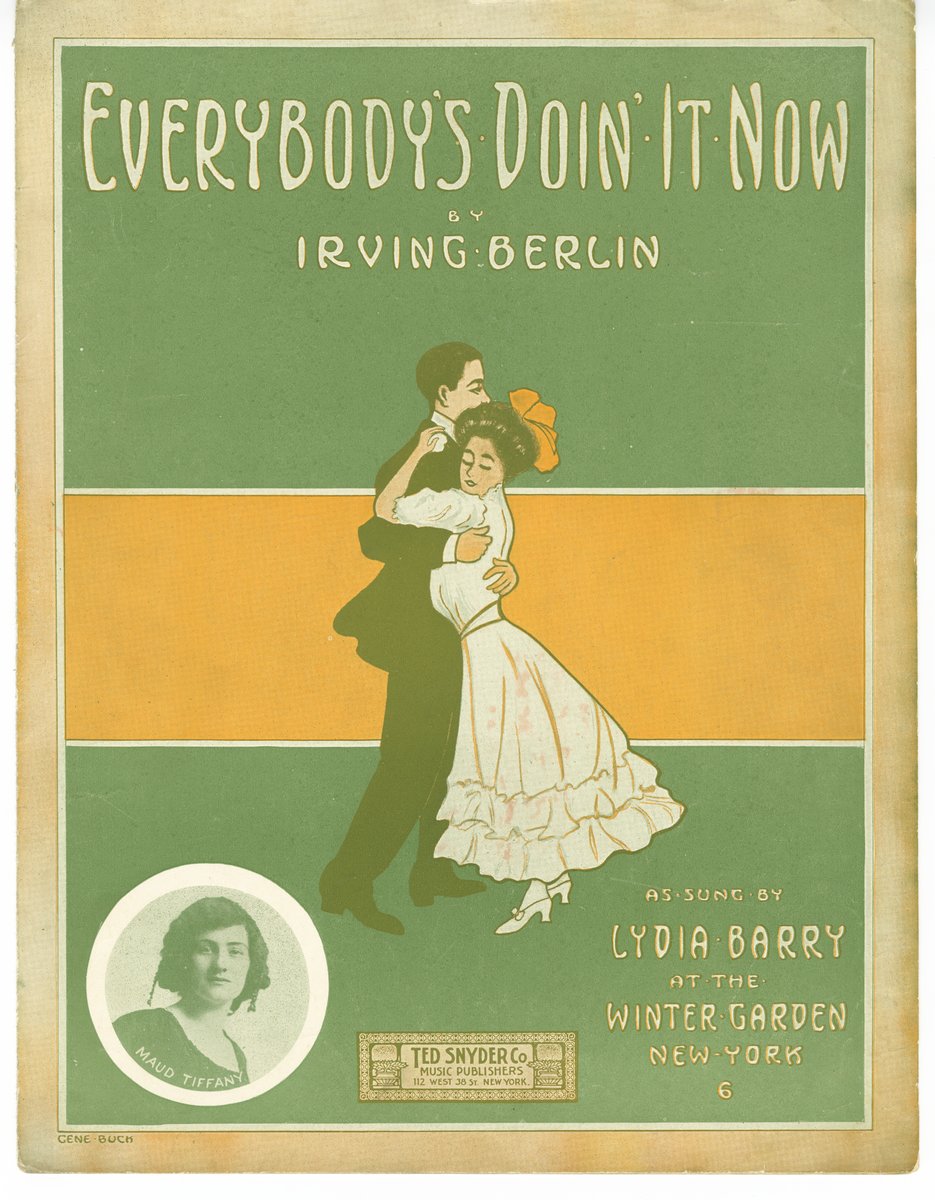

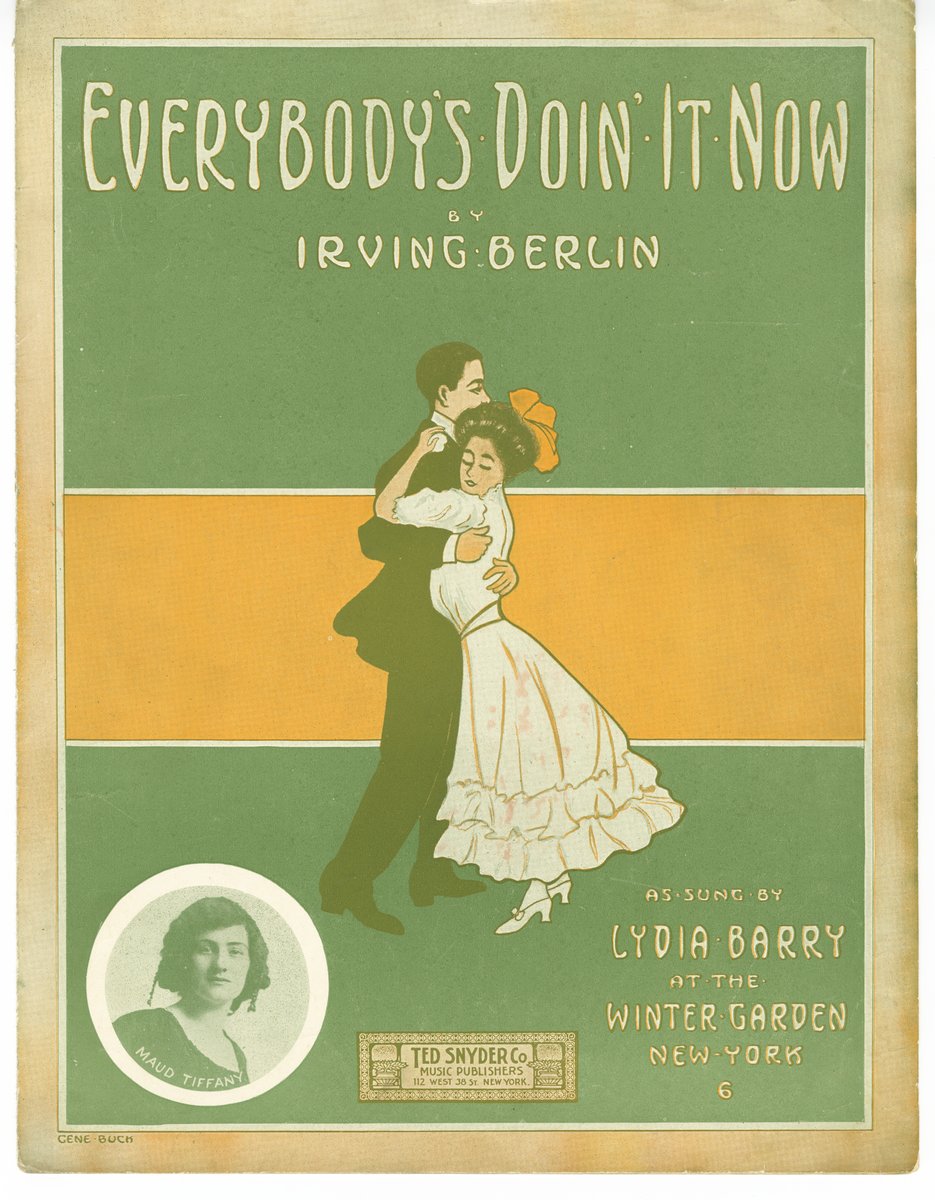

“Everybody’s Doing It Now” Lyrics

and Music by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1911 by Ted Snyder

Co.

“Everybody’s Doing It Now” is another

of Irving Berlin’s early hit songs that quickly became a standard. Purportedly

about a couple who are eager to take a spin out on the dance floor to a

snappy ragtime tune, the song’s lyrics also cleverly contain an obvious

double entendre that has certainly contributed to its lasting popularity.

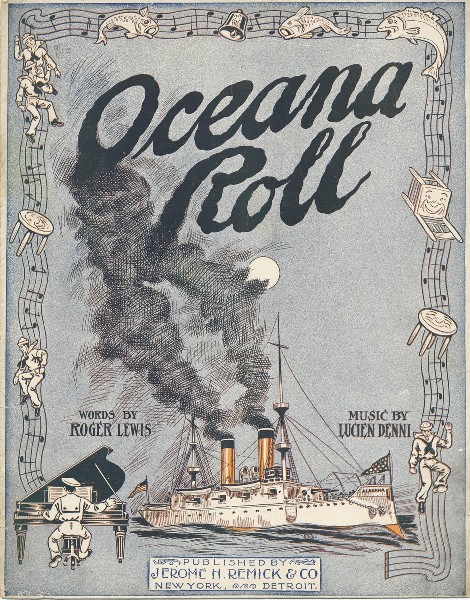

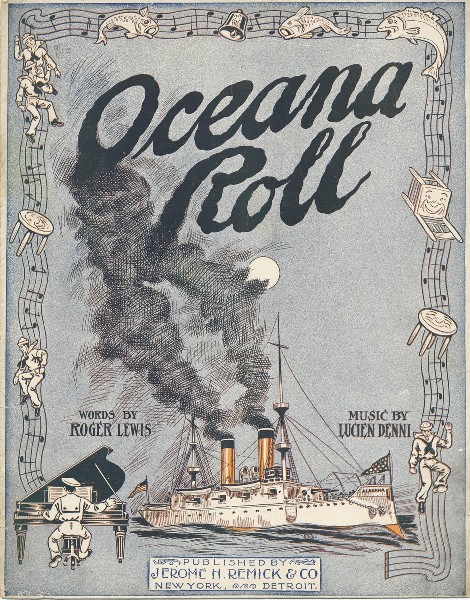

“The Oceana Roll” Lyrics by Roger

Lewis and Music by Lucien Denni

Copyright 1911 by Jerome H. Remick

& Co.

It is strangely fitting that “The

Oceana Roll,” one of the greatest ragtime songs, which tells the tale of

a shipboard pianist was written by a Frenchman. Lucien Denni (1886-1947)

was born in Nancy, France, but soon thereafter rolled his way across the

ocean toward the New World where he made his fame and fortune both as a

pianist in vaudeville and night club orchestras and as a composer. The

lyricist, Roger Lewis (1885-1948) was born in Colfax, Illinois.

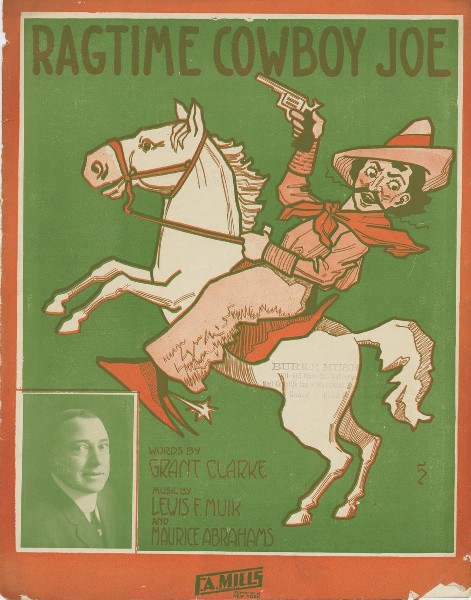

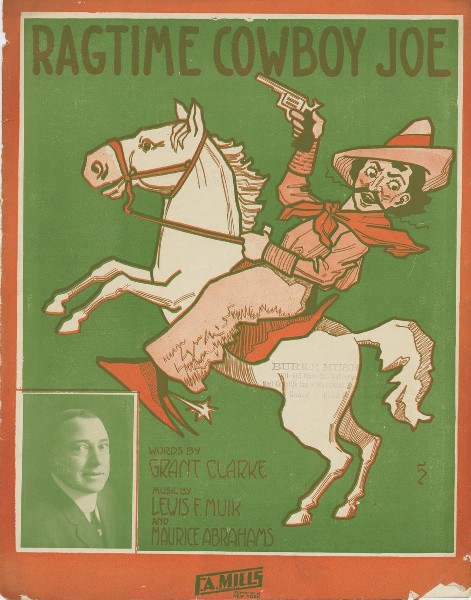

“Ragtime Cowboy Joe” Lyrics by

Grant Clarke and Music by Lewis F. Muir and Maurice Abrahams

Copyright 1912 by F.A. Mills

“Ragtime Cowboy Joe” was penned

by three of Tin Pan Alley’s top tunesmiths. Composer Lewis F. Muir (1884-1950)

was a ragtime pianist who performed at honky tonks in St. Louis on 1904

and in New York City in 1910. He was also an acclaimed performer in London.

Grant Clarke (1891-1931) began his working career as an actor in stock

companies, but soon found himself working as a staff writer at a variety

of music publishing firms. In addition to a steady outpouring of popular

songs, Clarke also wrote specialty material for Bert Williams, Fanny Crise,

Eva Tanguay, Nora Bayes, and Al Jolson. Maurice Abrahams (1883-1931) was

a charter member of ASCAP, who, in addition to writing songs, was a professional

manager of music publishing companies who eventually founded his own publishing

firm. “Ragtime Cowboy Joe” was a success when it first appeared in 1912,

but it too had a great future in store when Alice Faye sang the song in

the 20th Century Fox film Hello, Frisco, Hello in 1943. Betty Hutton also

gave the song her best shot in the 20th Century Fox film Incendiary Blonde,

a “bio-pic” about the life of boisterous entertainer Texas Guinan. “Ragtime

Cowboy Joe” is also the fight song for the University of Wyoming Cowboys.

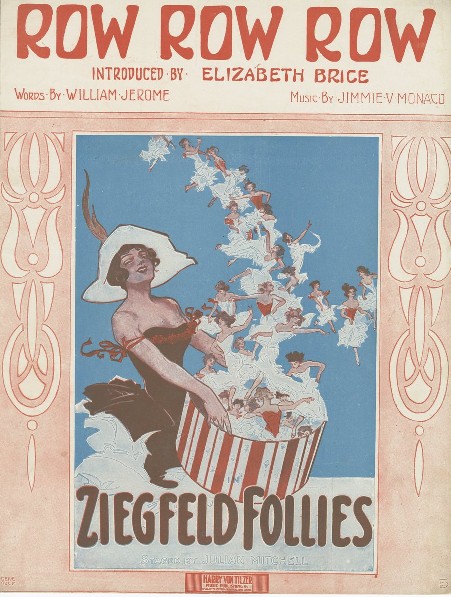

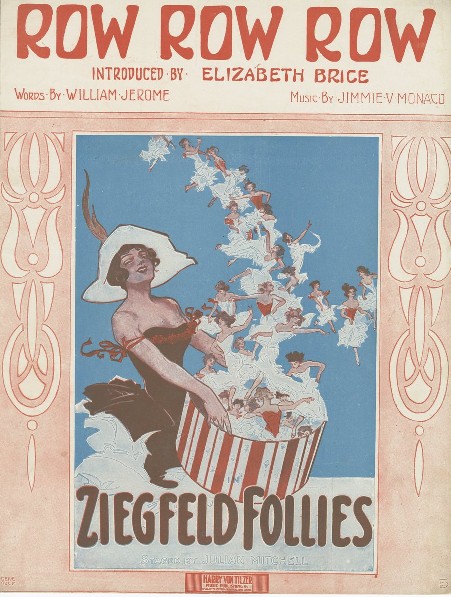

“Row, Row, Row” Lyrics by William

Jerome and Music by Jimmie V. Monaco

Copyright 1912 by Harry Von Tilzer

Music Publishing Co.

“Row, Row, Row” was the most popular

song featured in the 1912 edition of the Ziegfeld Follies and was introduced

by the charming Miss Elizabeth Brice. The song’s lyricist, William Jerome

(1865-1932), is best known for his enduring 1910 hit “Chinatown My Chinatown.”

James Vincent Monaco (1885-1945) was born in Fornia, Italy, but immigrated

to Albany, New York when he was six. He worked as a ragtime player in Chicago

before moving to New York. Monaco’s first successful song “Oh, You Circus

Day” was featured in the 1912 Broadway revue Hanky Panky. Perhaps his best

remembered song is “You Made Me Love You (I Didn’t Want to Do It)” introduced

by Al Jolson in 1913 and performed by Judy Garland with revised lyrics

as “Dear Mr Gable” in 1937. Monaco worked with a number of lyricists before

moving to Hollywood where he teamed with lyricist Johnny Burke to produce

songs for several Bing Crosby films.

“Snookey Ookums” Lyrics and Music

by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1913 by Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co.

Irving Berlin made light of the

challenges of apartment living in his classic “Snookey Ookums,” which humorously

address the thin-walled construction typical of cheap New York apartment

houses of the early twentieth century. Although there were many recordings

made of this song, the best may well be the comic duet by Arthur Collins

and Byron G. Harlan, preserved on Edison Blue Amberol (1796). Irving Berlin

himself performed “Snookey Ookums” to great acclaim in the summer of 1913

in the British revue Hullo, Ragtime! on the stage of London’s Hippodrome

Theatre.

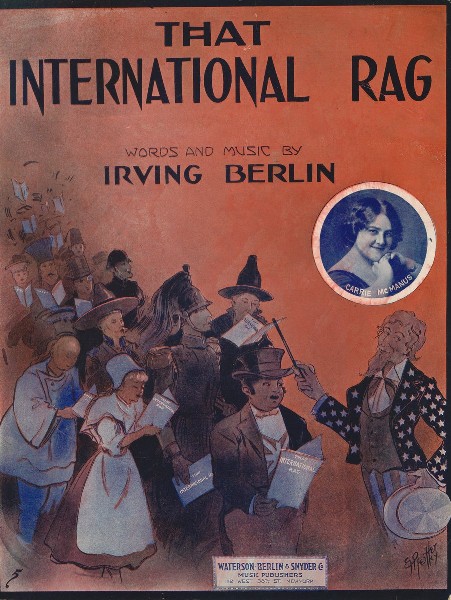

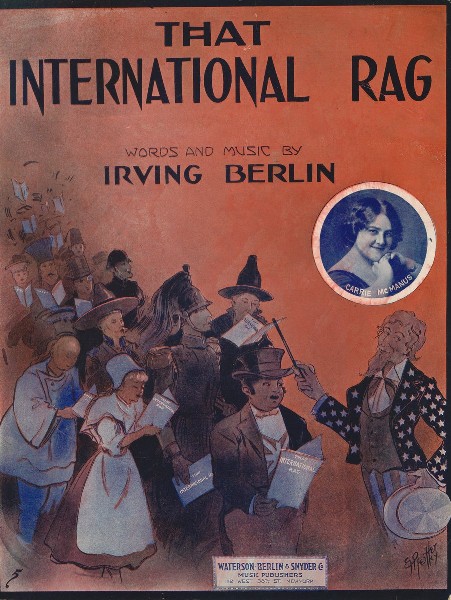

“That International Rag” Lyrics

and Music by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1913 by Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co.

Again, we find Irving Berlin writing

a legendary hit song that would be revived many years after its initial

success. Billy Murray may have made the best recording of this song in

1913 (2078: Edison Blue Amberol), but Ethel Merman belted it out in the

20th Century Fox’s 1953 film version of Irving Berlin’s hit Broadway musical

Call Me Madam. Alice Faye sang it with captivating charm in Alexander’s

Ragtime Band.

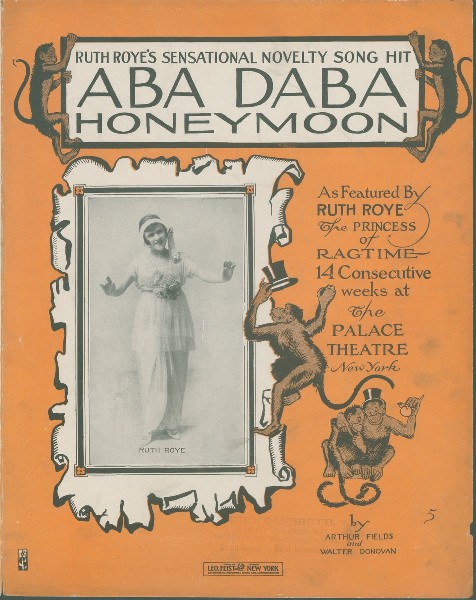

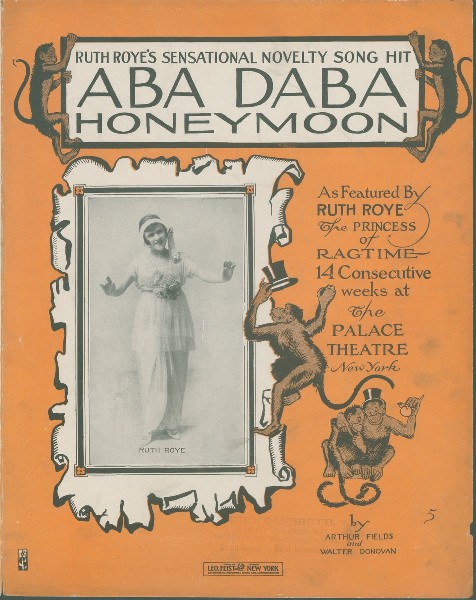

“Aba Daba Honeymoon” Lyrics and

Music by Arthur Fields and Walter Donovan

Copyright 1914 by Leo Feist,

Inc.

Known for its unswerving devotion

to exploiting fads, Tin Pan Alley’s craze for monkey songs reached a fevered

pitch in 1914 when vaudeville favorite Ruth Roye thrilled audiences at

New York’s Palace Theatre with what is arguably the best monkey song ever

written, “Aba Daba Honeymoon.” The lead author was Arthur Fields (1888-1953),

who was a favorite on the Vaudeville stage and a prolific recording star.

“Aba Daba Honeymoon” was revived in the 1950 MGM film Two Weeks With Love,

soon followed by the release of a popular Debbie Reynolds and Carleton

Carpenter MGM record (30282), earning Fields around $10,000 in royalty

fees in 1951. The song was first popularized on records made in late 1914

by Collins and Harlan (Victor 17620, Edison Diamond Disc 50192, Blue Amberol

2468).

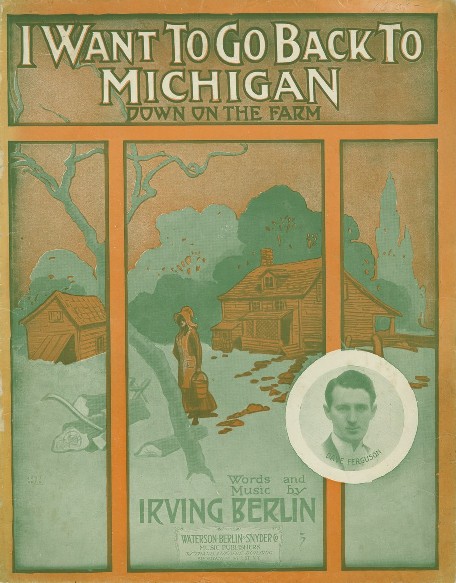

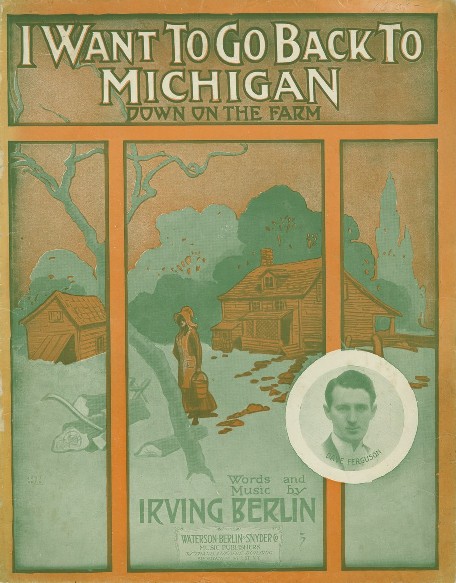

“I Want To Go Back To Michigan”

Lyrics and Music by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1914 by Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co.

“I Want To Go Back To Michigan”

is a charming Irving Berlin song that perfectly illustrates one of the

predominant themes in Tin Pan Alley songwriting: “The Homesick Urbanized

Rube.” Starting in the nineteenth century, the steady exodus of job-seeking

young men from rural areas to urban centers, especially the big industrialized

East Coast cities, was a notable demographic phenomenon. Presumably, these

young men were unhappy with city life and longed for the bucolic life they

left behind. Tin Pan Alley responded to this sociological situation by

churning out thousands of songs that addressed it directly. Irving Berlin’s

1914 masterpiece was a hit in its day and was also charmingly reintroduced

to America by Judy Garland in MGM’s 1948 classic Easter Parade.

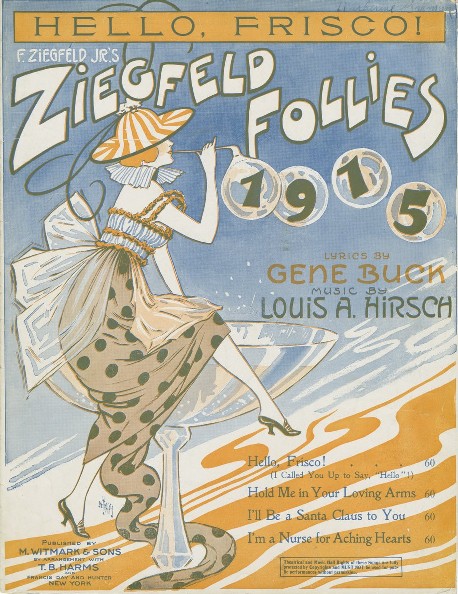

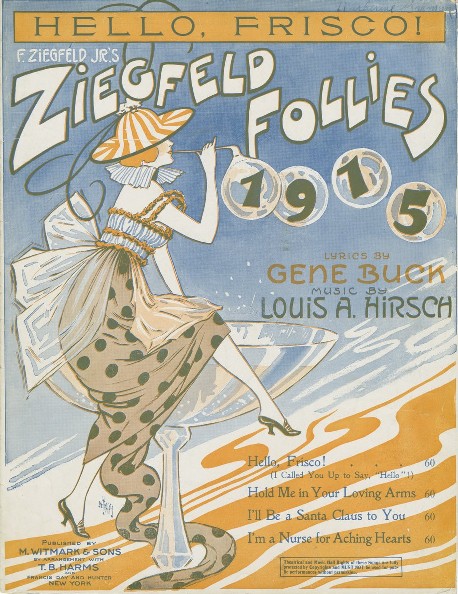

“Hello, Frisco!” Lyrics by Gene

Buck and Music by Louis A. Hirsch

Copyright 1915 by M. Witmark

& Sons

Celebrating the new transcontinental

telephone hookup, “Hello, Frisco!” proved that new technologies could be

a boon to romance. Situated at the New Amsterdam Theatre, the 1915 Ziegfeld

Follies featured sets by Joseph Urban. The opening sequence had showgirls

“swimming” in waves of blue light, and massive golden elephants spouting

real water through their upturned trunks. For the “Hello, Frisco!” number,

chorus girls appeared in costume as various cities now connected through

the miracle of modern technology. The song’s composer, Louis Achille Hirsch

(1881–1924) began his career as a staff composer for the Shuberts, but

by 1915 was enough of a success for Florenz Ziegfeld to invite him to contribute

a score for the Ziegfeld Follies. Lyricist Gene Buck was one of Ziegfeld’s

staff writers and also worked as a sheet music cover artist. “Hello, Frisco!”

instantly became the hit song of the 1915 Ziegfeld Follies. In 1943, the

song became a hit once again when it was featured by Alice Faye in the

lavish Twentieth Century-Fox Technicolor musical Hello, Frisco, Hello.

“If You Only Had My Disposition”

Lyrics by Charles McCarron and Music by Albert Von Tilzer

Copyright 1915 by Broadway Music

Corporation

This wonderfully naughty song, “If

You Only Had My Disposition,” could well have been written with Vaudeville

star Eva Tanguay in mind because it perfectly captures her saucy stage

persona. One of the best early recordings of the song was a duet by Sam

Ash and Edith Chapman on Columbia (A1868). Albert and Harry Von Tilzer

(1878-1856) dominated Tin Pan Alley during the first two decades of the

twentieth century. In addition to countless other hits, Albert’s 1908 song

“Take Me Out To The Ball Game” captured the heart of the nation and established

him as a megastar in the popular music realm. Charles Russell McCarron

(1891-1919) was prolific composer, a cartoonist, a pianist, and a Vaudeville

singer. He spent most of his musical career gainfully employed as a staff

composer at Albert Von Tilzer’s Broadway Music Corporation. He is best

remembered today for the 1919 jazz standard “Blues My Naughty Sweetie Gives

To Me,” which hit the music racks after his untimely death on 27 January

1919.

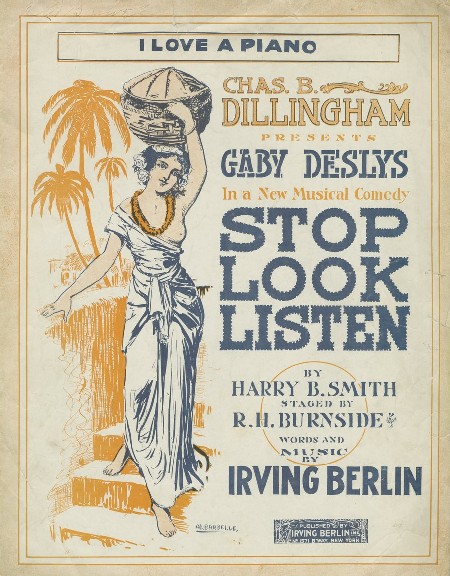

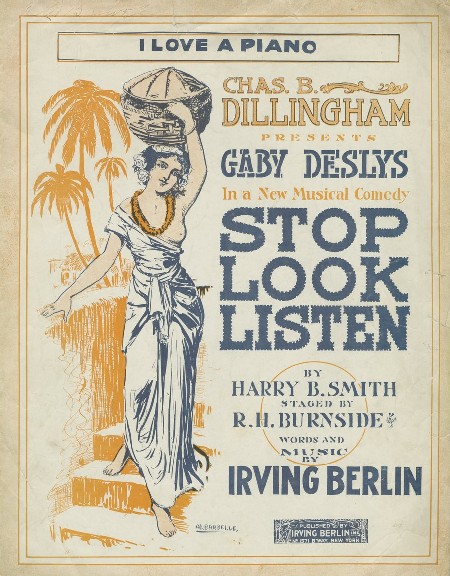

“I Love A Piano” Lyrics and Music

by Irving Berlin

Copyright 1915 by Irving Berlin

“I Love A Piano,” one of Irving

Berlin’s best songs, was first performed by Harry Fox and ensemble as the

finale to act one in Irving Berlin’s big stage production Stop! Look! Listen!,

which opened at the Globe Theatre in New York in late December 1915. Marion

Davies, the great film star of the 1920s and 1930s, made one of her earliest

stage appearances in the show. The song was charmingly revived by Fred

Astaire and Judy Garland in the spectacular 1948 MGM film Easter Parade.

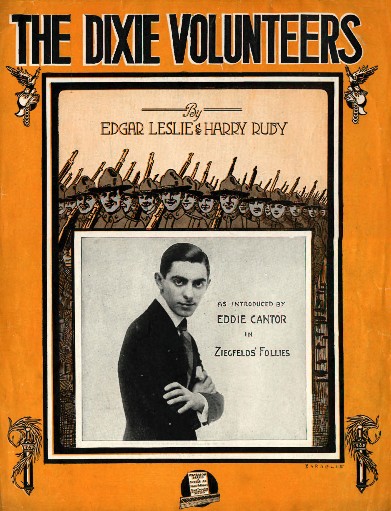

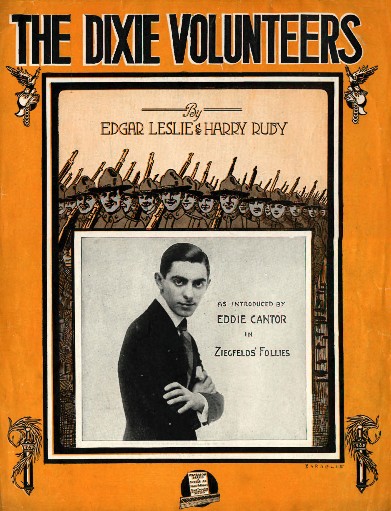

“The Dixie Volunteers” Lyrics

and Music by Edgar Leslie and Harry Ruby

Copyright 1917 by Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co.

In 1917, as the United States appeared

headed to join the war, patriotic sentiments ran high. Eddie Cantor introduced

a snappy war song into the Ziegfeld Follies that became quite popular.

“The Dixie Volunteers” was written by the song writing team of Edgar Leslie

(1885-1976) and Harry Ruby (1895-1959). Tin Pan Alley responded to World

War I by pumping out thousands of songs that fell into just a few broad

categories. “The Dixie Volunteers” is a “volunteer” song, which invariably

revolved around the military contributions of southerners and Blacks. Other

notable songs of this genre are “The Mississippi Volunteers” (1917) by

Levinson and Cobb, and “The Ragtime Volunteers Are Off To War” (1917) by

MacDonald and Hanley. These songs are snappy songs that advocate the idea

that Black American soldiers sent to Europe would win the war by just being

themselves and singing their native Dixieland songs.

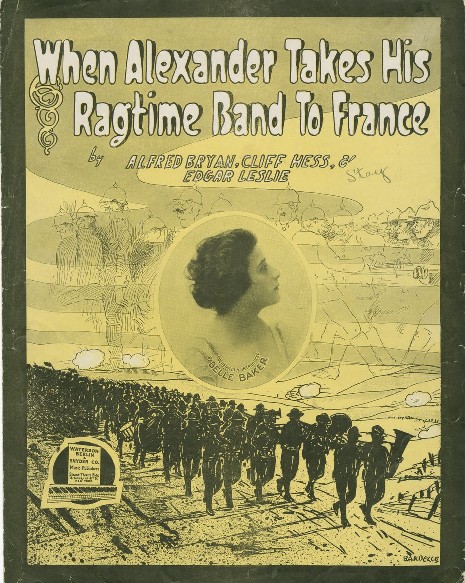

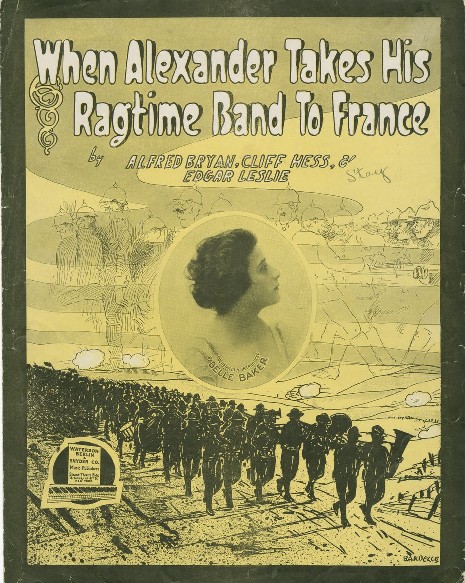

“When Alexander Takes His Ragtime

Band To France” Lyrics and Music by Alfred Bryan, Cliff Hess, and Edgar

Leslie

Copyright 1918 by Waterson, Berlin

& Snyder Co.

“When Alexander Takes His Ragtime

Band To France” is certainly one of the most enjoyable World War I songs,

most especially because it continues the saga of the mythical band leader

“Alexander” popularized by Irving Berlin in 1911. There were many songs

about Alexander, but this one is especially fun because of its suggestion

that the sound of American ragtime would make the German soldiers lay down

their guns and start dancing together on the battlefield “like picaninies.”

This is a play on the same theme espoused by Irving Berlin in “That International

Rag.” American song writers obviously were very impressed with their abilities

and were confident that they would transform the world through ragtime.

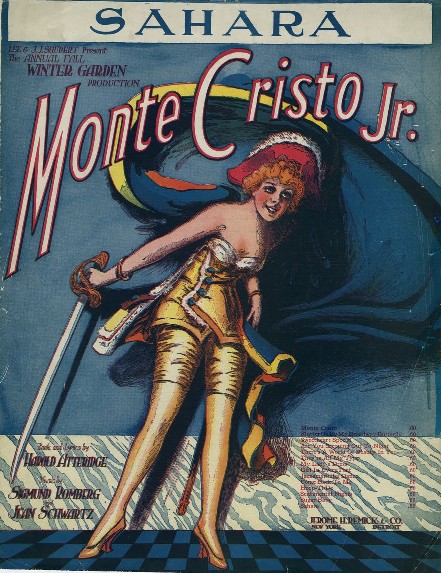

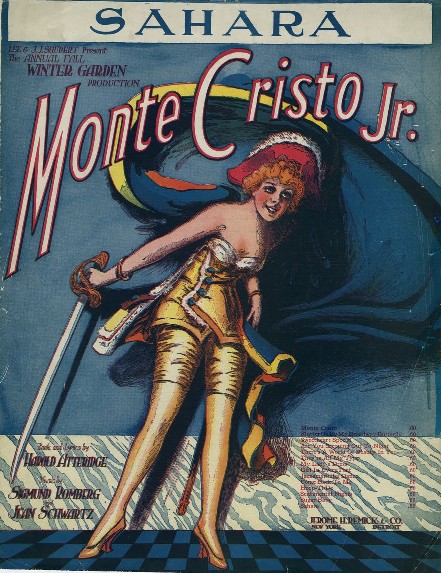

“Sahara (We’ll Soon Be Dry Like

You)” Lyrics by Alfred Byran and Music by Jean Schwartz

Copyright 1919 by Jerome H. Remick

& Co.

Monte Cristo Jr. was one of the

biggest and most succesful musical extravaganzas of the 1919 theatre season.

It opened 12 February 1919 at the Winter Garden Theatre and played for

254 performances. The score was nominally by Sigmund Romberg, but like

so many Broadway shows, it was spiced up with interpolated numbers that

injected a welcome bit of topical humor and levity. “Sahara (We’ll Soon

Be Dry Like You)” was as topical a song inspired by the impending passage

of the National Prohibition Act, “The Volstead Act.” This Act enabled Federal

enforcement of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on

16 January 1919, which banned the “manufacture, sale, or transportation

of intoxicating liquors” in the United States. This Act, was vetoed by

President Woodrow Wilson and over ridden by Congress overroad the veto

on October 28, 1919. Composer Jean Schwartz (1878-1956) was born in Budapest

and immigrated to the United States at the age of ten. Among his many hits

were “Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With A Dixie Melody” (1918) and “Chinatown,

My Chinatown” (1910). “Sahara,” however, is a song of remarkable and rare

sophistication. The chorus is a perfect example of “through-composed” music.

Most popular songs follow a 32-bar, A-A-B-A formula, consisting of four

eight-bar phrases. The first, second, and fourth eight-bar phrases are

roughly identical, while the third eight-bar phrase, known as the “bridge,”

is unique. In a “through-composed work,” however, no musical phrase is

ever repeated. Many examples of this form can be found in Schubert’s “Lieder,”

where the words of a poem are set to music, each musical line being different,

yet “through composed” music is very rare in American popular songs. The

only other examples of through-composed popular songsthat springs to mind

are the 1917 hit “Smiles” (by J. Will Callahan and Lee S. Roberts) and

Irving Berlin’s delightful 1924 song “Lazy.” Most fans of the song were

probably never aware of its unusual musical form, which is a testament

to Jean Schwartz’s musical cleverness. “Sahara (We’ll Soon Be Dry Like

You)” enjoyed tremendous success and was recorded by Billy Murray in November

1919 on Edison Diamond Disc (50638).

About the Performers

Singer Ann Gibson, who has

been crowned by her fans as “The Duchess of Ragtime,” has been gracing

Bay Area stages for over ten years with her velvety voiced renditions of

songs from the ragtime era through the 1930s. She has worked as vocalist

for the Black Tie Jazz Orchestra and the California Pops Orchestra. She

has also produced music reviews for the Art Deco Society of California

acclaimed for their originality of content and attention to authentic detail

in presenting popular music from the Art Deco Era. Miss Gibson was classically

trained as a child on piano, French horn, and also sang with several local

choirs. Her father, local band leader and composer Bob Soder, was instrumental

in her development as he exposed her to many different forms of music,

from classical to jazz.

Pianist Frederick Hodges is

well known to the ragtime world. He regularly performs solo piano and also

serves as pianist with the Don Neely’s Royal Society Jazz Orchestra. Frederick

is also a noted silent film accompanist and is regularly featured at silent

film festivals around the country and also serves as one of the house pianists

for the Niles Essanay Film Museum. Frederick is a favorite at jazz and

ragtime festivals around the country. More information can be found at

his website: www.frederickhodges.com